Translingual Creative Writing

ILFU Workshop 2: Queer Code-switching

Obe Alkema. Photo: Jared Meijer

By Jared Meijer

Following an intimate, enervating workshop by the poet Dong Li, on “Translation as Creative Inspiration”, the second workshop in this series centered around “Translingual Creative Writing”, held at the main office of the International Literature Festival Utrecht, examined the practice of “Queer Code-Switching”. The workshop took place on 19 January and was led by the poet Obe Alkema in conversation with Utrecht University linguistics researcher Hielke Vriesendorp. Alkema, editor at publisher AnkhHermes and author of the glossies-cum-poetry-collections Obelisque (2018) and Obelisque (2022), as well as the chapbook Gênante Nabestaande (2023), opened with a reading of his poem “YOU ARE A WEAK SLUT. DON’T HIDE YOUR AMBITIONS”. English slang permeates throughout the poem, co-mingling with its “native” Dutch:

[…]Ik heb mijn teenage wasteland weten te veranderen in een black hole of narcissism.

De aanzuigende werking, de aftuiging.

Siri, why does God allow suffering? Siri, why can’t you answer all of my Qs?

Hooggevoeligheid. Toen ik mijn nieuwe Happy Socks aangetrokken had, voelde ik me niet happier.

Hooggevoeligheid. Ik vond twintig euro op straat en voel me hetzelfde.

Ik moet met mijn eigen bestaan geconfronteerd worden.

De luwte, de wanorde. Ineens blijk ik een persoonlijkheid te hebben!

Guitige blik, guitige buik, Does the tribe really describe you?

[…]

This segment of Alkema’s poem demonstrates many of the topics touched upon by Alkema, Vriesendorp and the workshop group. In reading the poem, it is immediately revealing how code-switching could be regarded as an “identity practice,” which Vriesendorp has elaborated upon his essay co-written with Gijsbert Rutten, “‘Omg zo fashionably english:’ Codeswitching to English as an identity practice in the chatspeak of Dutch young gay men.” The speaker in Alkema’s poem sheds his “teenage wasteland” for the no-less lonely “black hole of narcissism”, though it is by virtue of this lostness being embedded within a different language, that it is all the more palpable. At the same time, we read these phrasings as representative of the narrator’s everyday diction, that of a type of person.

As Vriesendorp and Rutten describe it, code-switching as an identity practice is a mode of using alternative languages, particularly Internet English, within the context of a dominant local language to signal resistance to the normative local culture and to define one’s identity within one’s own peculiar, personal, performative terms. So too does Alkema’s poem employ a performative peculiarity to shape its identity, and signal where it does and does not belong.

During the workshop, Alkema also presented “YOU’RE A WEAK SLUT” alongside an all-English translation, wherein the Dutch has been translated, but the code-switched language remains unaffected. The group noticed that it effectively nullifies the poem. As the code-switched language is assimilated into a monolingual context through translation, tensions dissolve, and playfulness becomes kitsch.

The conversation between Alkema and Vriesendorp during the workshop delved further into code-switching as a means of signalling belonging. The practice itself is associated with and often borne from and within subcultures and marginalized groups within society. It may signal an in-group position and may even be a coded way to message to one another within or when among the world at large, a world that may be hostile or judgemental. Code-switching may also be a tool to join in shared marginalized experiences, and participate in a grander, extranational context, borrowing language or coded terms from an international community, or, as is the case here, U.S. American and Western media, to try and break through isolation.

But then again, “Does the tribe really describe you?” The conversation between Alkema and Vriesendorp paid special attention to young queer people who, to varying degrees, (subconsciously) turn to code-switching as they look for a sense of belonging within a globalized queer culture. However, Alkema and various participants of the workshop also pointed out that the kind of code-switching employed by Dutch queer communities can also be seen as either building solidarity with or an appropriation of language associated with the African American community. We were invited to read the piece “To Blacken” by John Keene, wherein he writes:

If mainstream language is the living structural form of linguistic code, and if code is the standard set of symbols and their relations […], then hacking the main stream, blackening the code involves a switching, in it, blacking it (in)

For Keene, as it is for Alkema, code-switching is about subversion, breaking away from existing relations of domination. As we read later: “blacking it is deforming it and reforming it, farming its sets into new relations and forms”. Within Alkema’s poetry, code-switching performs similarly, especially as its co-opted language produces myriad rich new tensions and relations, enriching it. Alkema’s work is presented in the formal subversiveness of glossies and marks a different, hybridized mode of being in the world.

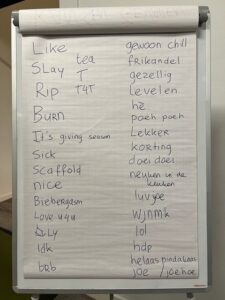

Finally, after we read the various poems and discussed the potential of code-switching, we worked on the writing prompt offered by Alkema. Together, the group made two lists, containing Dutch and the English culturally-coded terms and pieces of slang, respectively. Participants were challenged to construct a poem using the terms from one of the lists and to embed them within another language, not necessarily Dutch or English. The contributions were varied, tackling the alienating slang of Dutch grocery shopping, or that of a cyborg deciding what body parts to keep—a conjoining of self and other. And so we swerved back and forth, breaking open language, highlighting the literary potential of code-switching through its production of meaningful encounters.

You must be logged in to post a comment.